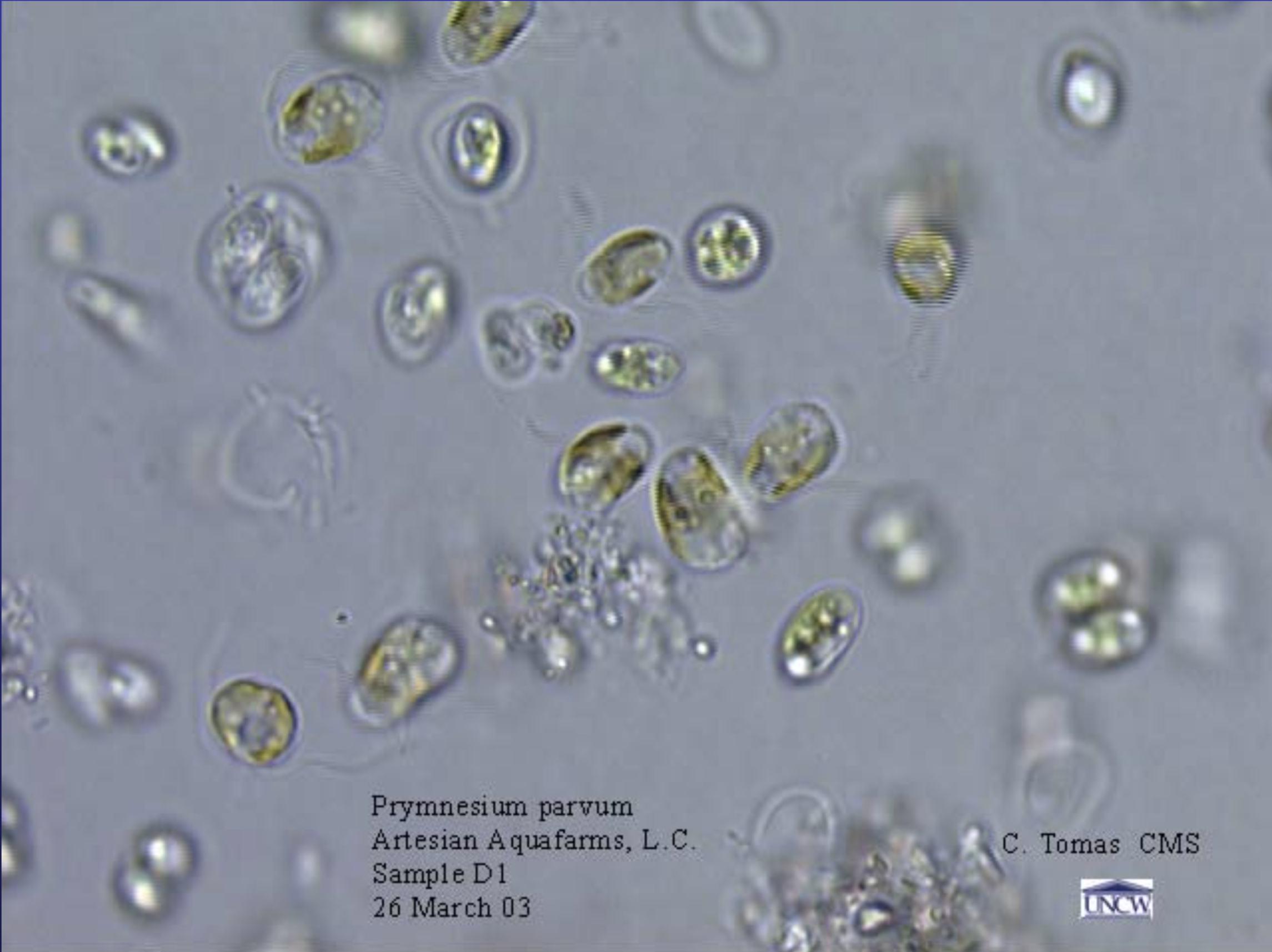

Golden Algae, Prymnesium parvum

Of the non-cyanobacterial inland HAB taxa, Prymnesium parvum is likely the most problematic in U.S. waters. This unicellular haptophyte is tolerant of a wide range of salinities and temperatures, making it suited to environments ranging from brackish coastal waters to inland rivers and streams. Blooms of P. parvum can stretch for hundreds of kilometers, and are often monospecific because this alga consumes other competitors in the ecosystem. At high cell densities the water takes on a golden color, giving these blooms their common name, “golden alga.” It is important to note that there are also non-toxic strains of this species, therefore the appearance of a golden bloom does not always mean that the water is toxic. Conversely, low densities of highly potent P. parvum can impact ecosystems even if a bloom is not visible.

While P. parvum is best known for causing massive fish kills, toxins from these species can also kill larval amphibians and bivalves. Prymnesium parvum produces multiple kinds of toxins, some of which become more potent once they are released into the environment after the cell dies. Some toxin forms are light-sensitive and will break down in sunlight, others are rendered less harmful at lower pH levels. Affected fish display bleeding gills and mucus, and exhibit behavioral changes including slowed swimming or attempts to leap out of the water and onto shore. Species impacted by P. parvum include catfish, carp, gar and bass. Recovery of fish populations is dependent on the duration and frequency of P. parvum blooms, as well as the fecundity and mobility of the fish species.

Prymnesium parvum blooms occur worldwide, causing mortality events in Europe, Asia, and even Australia. In the United States, Texas has been particularly affected by P. parvum blooms, which were first documented in 1985. The majority of major kills have occurred since 2000 as this toxic alga has been found in an increasing number of river basins in the state; annual events have occurred in the Colorado River drainage since 2001. Prymnesium parvum has also been confirmed in New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Arkansas, and Alabama and has been suspected in Oklahoma and Nebraska. In New Mexico, P. parvum has entered into stream environments where it threatens the survival of the Pecos bluntnose shiner, which is listed as a threatened fish species.

These blooms can last many months, hindering recovery of fish species and inhibiting recreation. Local communities have experienced huge financial losses as tourists avoid impacted areas and fishing guides lose their customers. Prymnesium parvum poses a threat to cultured as well as native fish in rivers and lakes. In the 1940s, it caused significant fish mortality in Israeli aquaculture ponds. In 2001, P. parvum killed the entire year's production of striped bass at Texas' Dundee State Fish Hatchery with over 5 million fish lost. Blooms of this species continue to threaten the health of farmed fish, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Additional Resources:

- Henrikson, J.C., Gharfeh, M.S., Easton, A.C., Easton, J.D., Glenn, K.L., Shadfan, M., Mooberry, S.L., Hambright, K.D. and Cichewicz, R.H., 2010. Reassessing the ichthyotoxin profile of cultured Prymnesium parvum (golden algae) and comparing it to samples collected from recent freshwater bloom and fish kill events in North America. Toxicon, 55(7), pp.1396-1404.

- Southard, G.M., Fries, L.T. and Barkoh, A., 2010. Prymnesium parvum: The Texas Experience 1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 46(1), pp.14-23.

- Yates, B.S. and Rogers, W.J., 2011. Atrazine selects for ichthyotoxic Prymnesium parvum, a possible explanation for golden algae blooms in lakes of Texas, USA. Ecotoxicology, 20(8), p.2003.